A son in Europe chapter I

The following day, at 6am, his phone rang again: “mother’s dead,” his brother said. Mother’s dead. Mother’s dead. Mother’s dead. Even today, four years later, this sentence echoes in Francisco’s head. The flight from Senegal to Portugal – alone, scared, without a visa. His body was shivering from the cold, as he waited in just a cotton t-shirt at Lisbon Portela Airport for the bus that would take him to the Benfica training ground. The matches in which there would be no one there to support from the audience, the loneliness of holidays spent with the doorman. Suddenly the main reason he had, at the tender age of 15, gone all in for a football career in Europe had vanished. “She was everything to me. What I wanted more than anything was to give her a better life. I dreamt of building her the house she deserved, sorting her out some decent clothes, doing things so that my mother could say, ‘Francisco, what I did for you was worth it.’”

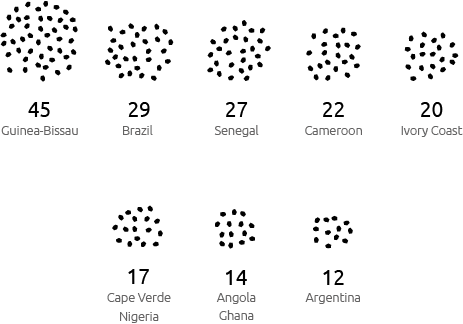

Francisco Junior is from Guinea-Bissau; he was born in the capital Bissau 23 years ago. At the age of ten he started to receive offers from the agents who take boys from Africa to try their luck at European football. He is one of at least 226 Africans (the majority from Guinea-Bissau) now playing in European competitions who left their continent as minors, chasing the dream of one day becoming professional footballers. One of the 294 African and South-American players who dodged the International Football Federarion (FIFA), and arrived in Europe as minors.

“FIFA has a general rule: the international transfer of players under the age of 18 is not permitted because it is understood that before they reach adulthood they need to develop areas of their personal life. What happens is that each country’s migration law [which, in the majority of cases, allows the free circulation of minors as long as they have parental consent] takes precedent over FIFA. In my opinion, the people who are not doing their bit are the National Football Federations who should force clubs to follow the rules,” says João Diogo Manteigas, a lawyer specialising in sports law.

Mother always said no, that he was too young. Only if they took them all. However, Francisco’s father, Francisco da Silva, never denied that it was what he had always wanted: “to have a son in Europe earning money to invest in his country is what all Bissau-Guineans want,” he confessed while sat on an imported leather sofa, in the new house that his son paid for him to build in Bissau.

It seems that promises of easy money to a seven-person family who live on less than a euro a day can buy anything – even a son. Football was always a dream, yes, but also the only opportunity that Francisco found that would enable him to help himself and his family. “Life in Africa isn’t easy. Every day is a struggle to survive. Life in Africa isn’t easy at all.” He repeats this cliché countless times, as if repeating it might alleviate the situation, as if it could change something.

Francisco Junior grew up in the Bairro Militar, on the outskirts of Bissau. Ever since he can remember, he was up at six to sweep the house. Afterwards, with a tray that his mother placed on his head, he would go out onto the streets to sell whatever they had: bananas, bread, salt. “Money went directly to mother so she could buy something to go with rice. Most of the time we just had white rice. She achieved the impossible to put food on the table,” he tells us from the top floor of a building with a 180-degree view over the city of Liverpool, England, where he now lives.

It used to take him two hours to walk to school, crossing a river. As he had no money for transport, he used to take a spare pair of shorts to change into when the others got soaked crossing the body of water. At the end of school, it would take him another hour and a half to get to training sessions at the Lino Correia stadium, where Sport Benfica de Bissau plays. On a still empty stomach, with tired legs and sore feet from the plastic shoes he used for playing. He used to train hungry. Dinner was often his first meal of the day.

Sellers of dreams chapter II

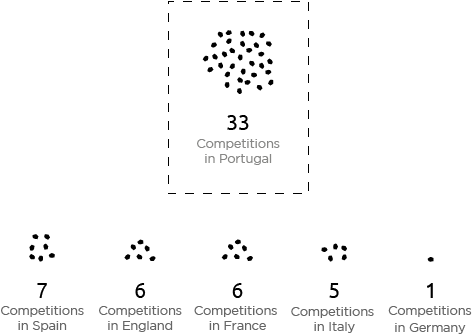

When Francisco, aged 14, started making waves at Sport Benfica de Bissau, the first serious invitations arrived: Sporting Lisbon and FC Porto were interested. Portugal is the first port of entry for these players. Forty-nine African and nine South-American minors played in the main European clubs during the 2014/2015 season. Over half were playing in Portugal. The three big championship clubs – Benfica, FC Porto and Sporting – are the clubs which had the highest number of minors from these continents on their squads. “Portugal is, for better or worse, an exceptional platform for this type of business,” explains Joaquim Evangelista, the Chairman of the Portuguese Professional Footballers’ Union (SJPF).

“The first agent who hired me was Juca Fernandes (also from Guinea-Bissau). The news that I was going to be brought to Europe was on the radio at all hours. Getting to Europe was like reaching the sky. I thought ‘I’ll never come back’. I had the notion that people here [in Europe] didn’t need to try, that they didn’t have to do anything… But in the end it didn’t work out,” Francisco says.

More than selling a boy with talent, what agents really want is to earn as much money as possible, and Francisco’s family had nothing to offer. “As we were poor, they would come and negotiate the invitation that had been offered directly to me with families who had more money. They would take another boy in my place.”

“Catió has treated people the same way for years and he is still successful,” he says. Catió Baldé is the agent responsible for a large proportion of the footballers from Guinea-Bissau who play in Europe; as João Diogo Manteigas puts it “the nerve centre for transfers in Guinea-Bissau.” “He is the most influential agent with the greatest success rate in Guinea-Bissau’s history in terms of player transfers to Portugal,” the lawyer adds. Often it is the families themselves who go to the agents asking for help. “They can show more interest than the agents themselves. Their only concern is making money from the players. They take their cut and they don’t want to know anything else. Knowing that their son is going to Europe makes Bissau-Guinean parents happy,” Francisco explains. His father was no exception.

Catió Baldé’s invitation arrived in January 2008, while Francisco was playing in the Guinea-Bissau national team in Dakar, the capital of neighbouring Senegal. It was the first time that the agent had contacted Francisco directly:

“Benfica is interested and is going to send someone to Senegal to bring you over.”

He had been hearing the same story for four years. By now he didn’t believe that it would ever happen. The telephone rang again:

“Francisco, you know what to do. You either go, or you stay. Either you go back to Guinea-Bissau or you stay in Senegal and travel to Portugal,” Baldé finished.

Francisco had no money on him apart from what the Bissau-Guinean national team coach, Pedro Dias, had given him to get back in case anything went wrong. Stuck in his mind was his “obligation” to give his mother a better life. Mother, always mother. It was dreaming of everything that he would be able to buy – food, clothes, the new house – that he boarded that plane without a visa. “Even today I don’t know how I got through… I arrived, showed them my passport and everything was fine. When I got to Lisbon, they stamped my visa.” He was 15 years old.

Goodbye Bissau, hello Lisbon chapter III

When he left Lisbon airport, he knew for the first time what it felt like to be cold. He spent thirty minutes waiting for the bus that would take him to the Benfica training centre in Seixal, dressed in just a cotton t-shirt and trousers. “I don’t think I’ve ever shivered so much in my entire life. Afterwards, I was welcomed; there were other Bissau-Guineans there, lots of Africans…,” he remembers.

One day in Portugal and he already wanted to go back. He missed everything, even washing with cold water and the bedroom with no lighting. In his new house chats on the porch with the neighbours were conspicuously absent, as was the noisy laughter, his mother’s love. “People were different. In Guinea, when we woke up in the morning, we were all together. Here everyone slept separately. Only God knows what I went through. I called my mother and she started to cry. ‘If you aren’t happy, come back. Come back, come back, please,’ she said. I was always a very spoiled boy.”

After two, three months, he settled in: bed, food, clean clothes, training and language lessons – French, English and Portuguese. “I even started to go to Year 9 classes, but I had to give them up because of training.” He didn’t think about going back anymore. Benfica paid him 400 euros a month; he used to send 300 to Guinea. Catió Baldé never paid his family the amount he had promised and Francisco felt obliged to help them. This is a cycle of dependence that continues today.

“When I signed my first contract, the document said that a part of the money should go to my parents and to Benfica de Bissau (the club where he started out), but this money never arrived. The agents took it. When signing, they offered clothes and material goods, but then you never see them again. Years pass and you start to understand that you were and are being exploited.”

In various public statements, Catió Baldé has said that he feels like a “father to these boys.” But Francisco swears that he never saw him like that. He was forced to grow up, he experienced many difficulties, but he doesn’t regret it: “Benfica got me out of Africa. I owe the club an eternal debt. Catió was the man who brought me and I thank him for that, but I never thought of him as a father.”

His worst moments were when Christmas or other important holidays came around: all his team mates with their bags packed waiting for their family who arrived, smiling, in their cars. Meanwhile Francisco would be sat on the kerb, watching from a distance this affection that he also longed for.

He knew of some people who had come to Portugal from Guinea-Bissau and he tried to contact them on Facebook, but few responded. Despite everything, he swears he was “lucky”. His “luck” was to never be thrown out of the club where he played. To have always had somewhere to sleep, clothes to wear and things to eat. To never have been chucked out onto the streets in a country that is not his own and where he knew no one. “I know many agents who choose the boys, take the money, leave them in the clubs and then leave. You cannot pick up someone else’s son, take him, and then never think about him again just because he’s African. They tell us they’ll change our lives and then, when we get to Europe, they take the money and they’re not interested anymore,” he says. After a short period of time, a lot of these children are let go. They get injured, they don’t adapt quickly enough or they fail to meet expectations. They are completely alone, with no one to take them in; sometimes they sleep on the streets.

Francisco recognises that coming to Europe was the best thing that happened to him, but he doesn’t agree with the current system. He swears that he won’t stop speaking out until he has no voice left: “I’m not scared of anyone. I don’t depend on anyone – just my own two feet. It’s wrong to bring kids over from Africa and abandon them in Europe. Because when I say abandonment, it is abandonment. Utter abandonment. We are talking about children. I repeat: a child! A boy who isn’t old enough to be a man.”

He is not against aspiring footballers coming, but he is revolting against the way they are brought, being treated as “merchandise”, being enticed by the promise of a future that may never become a reality.

The weight of a family capítulo IV

He is now, he declares, “old enough to be a man”, but this doesn’t lessen the emptiness he feels inside. For a long time loneliness has been his greatest ordeal. “I live alone, I have no one. If I have a problem, I am alone; if I am sick, I am alone; if I am sad, I am alone. If I need to vent about something, I have to vent at myself. If my families have problems back home, I have to resolve them. They have to go to school, to dress, to eat. It’s a lot of things for one person to have on their plate,” he admits.

He has realised his dream: he plays for Everton, a club in the English Premier League, he lives in a two-bedroomed apartment on the marina in Liverpool, he drives a BMW X6, he wears Nike trainers. For special occasions, he wears Armani. Some months he can send up to a total of ten thousand euros to Guinea-Bissau, split between his father, brothers, uncles, cousins and neighbours. More than 20 people depend on him. “Africans think that anyone who goes to Europe automatically becomes rich. Many don’t go back to their country because they didn’t get rich enough to look after those who are going to ask them for money.”

Francisco built a house for his family in Bissau, he bought a taxi for his dad – which he rents and adds to his teacher’s salary (around 150 euros) -, he pays for the school, food and housing for his four brothers who study in Senegal and he sends money whenever there is an emergency. Even so, his father, Francisco da Silva, says that “in his heart” he is still not satisfied.

Francisco earns 30 thousand pounds per month (about 40 thousand euros), not counting any sponsorships and player awards. “I try to save as much as possible; I’m here today, but I don’t know about tomorrow.” He doesn’t permit himself many luxuries. His routine doesn’t stray far from training, Playstation games and his iPhone, a seemingly inseparable extension of his body. Music – that varies between Kisomba, Rap or Pop – is also ever present, as if life ceases to exist without a constant soundtrack. Having a few whiskies and singing karaoke in private clubs, smoking shisha or having dinner at Nando’s are his escapes. He lives a monotonous and frugal life.

“To be a footballer, you sacrifice a lot. The first thing is your youth: you don’t have fun like a normal kid. You only have ten, or a maximum of fifteen years, depending on how you look after your body. At any moment you might get injured, and you may never be the same again. When you are an African player, it’s even more complicated.” After nearly ten years in Europe, now he doesn’t pay any attention when people use the colour of his skin to insult him on the pitch. “Even today during training they called me nigger mother fucker. I’m immune, I let it go over my head.” He got it into his head that to achieve the same thing he would have to work twice as hard. Is that fair? “No, no it isn’t. But the world isn’t fair. Anyone who thinks it is should find another planet.”

I’ve never been richer, I’ve never been poorer chapter v

Francisco hasn’t forgotten everything he has been through and feels that he should help other children who, like him, came to Europe chasing a dream but ended up without a club. He worries about them, takes them in, and cares for them. Batis is part of the furniture in his house in Liverpool. He was one of the promising young stars at Benfica in 2012. He got as far as playing in the Portuguese national youth team. Then he got injured and ended up without a club. This same story repeats itself times without number. Batis cries when, on the other end of the line, his mother asks for money to buy a bag of rice and he can’t help her. In Francisco’s apartment, he eats, sleeps, plays videogames, listens to music, goes on the internet. When he wants to go home, Francisco either pays for a taxi or takes him back; he also gave him money to send to his family in Guinea-Bissau. “I understand the desperation he must feel. In life you can be fine today, but not tomorrow. I like to help. Money can help sometimes.”

Money for money’s sake doesn’t interest him. When he left Guinea-Bissau, he never imagined that his bank account would ever reach so many digits. When he left Bissau, he also never imagined that he could feel so poor. He has never been back to the house where he was born; he rejects everything that reminds him of the person he loves the most. The only thing he wanted was to have seen his mother dressed in the clothes he had bought her in a European shop, to live in a brick house, to serve her a rice dish full of all kinds of fish. If that afternoon he had not been so lazy, if he had gone to the Western Union in Lisbon to send the money, perhaps it would have still been possible. He’ll never know. Theses ‘if’s are the ghosts that he has had to learn to live with. “The only thing that I wanted was to see my mother smile, to say ‘thank you’. But I didn’t manage it. So I will never be happy for the rest of my life. I can have everything, but I will never be happy for the rest of my life.”

Este menino-homem é um grande exemplo de ambição e querer. Conheci-o com 15 anos num torneio em Brasília representando a sua Guiné e foi ter comigo pedindo ajuda para ir treinar em Lisboa no “seu” Benfica. Falei com Nené e Rui Águas, abri os contactos e tempos depois soube da sua afirmação como jogador de talento. Felizmente deu certo, Mas foi pelo seu empenho e inteligência pois quem andou à volta dele por interesse quase lhe arruinava a carreira, soube eu depois. Fico muito feliz por ver como ajuda a família e consegue amealhar pensando no futuro. Não tenho dúvidas que vai saber gerir bem o que conseguiu até agora. Deus lhe dê sorte e ventura. Ele bem merece. Prometeu-me fazer uma visita. Espero por esse reencontro.